Culture@Work

Welcome! My name is Joost Thissen and I am an Interculturalist. Here I share intercultural insights for those of us who work in culturally diverse and global workplaces.

Welcome! My name is Joost Thissen and I am an Interculturalist. Here I share intercultural insights for those of us who work in culturally diverse and global workplaces.

cultural column  Email This Post

Email This Post

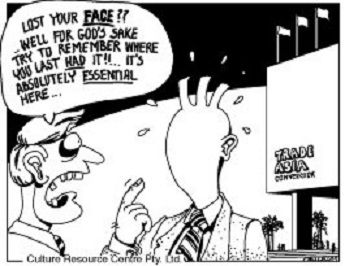

‘Face’ can be explained by the way we present ourselves to others, it determines how we are judged and how we want to be perceived by others. According to Earley, it is a fundamental part of human interaction, and it can be seen as a reflection of the individual’s struggle for self-definition and understanding.

‘Face’ strongly relates to the cultural understanding of a persons’ respect, honor, dignity and social standing.

Consider the following scenario:

A Dutch Project Manager, working for an US company based in Singapore, was more than ready for the upcoming team meeting. Her American colleague, the Senior Project Director of her team, had managed to avoid her over the past few days. He recently decided to ignore serious ethical business protocols in order to win a business deal. None of her team members agreed with his decision but no one had spoken up to him.

Head-on collision

In the meeting, the Dutch manager confronted the American head-on: “You know very well that we don’t conduct business in this manner. What you did was unethical and extremely unprofessional. Also, If word got out…”. You could hear a pin drop. A Hong Kong colleague was suddenly extremely interested in an article in front of her, two Singaporean Chinese colleagues were studying something on the wall, and the Malaysian project assistant looked simply distressed.

The American did not respond at all, and moved to the next item on the agenda. The Dutch manager lost her temper and angrily asked her team members to voice their opinions, but nobody seemed to think that this was such an important issue anymore.

What is being ‘right’ after all?

By questioning his ethics, and pointing out his unprofessional behaviour, the Dutch manager had caused the American to ‘losing Face’. As a result, she lost a lot of trust and goodwill from her Asian team members, which she had so carefully developed over the past months.

Although convinced that she was morally ‘right’ to raise the issue, she found out that being morally right was not as important as using the ‘right’ approach within this cultural context. In fact, she had not given the required amount of face: she caused her American superior to lose respect, dignity and social standing in front of the Asian colleagues. This comes close to unacceptable behaviour in some cultures.

Westerners sometimes regard ‘losing Face’ as a simple case of personal embarrassment. When a Westerner is ‘losing Face’, feelings of guilt usually enter the spectrum. However ‘losing Face’ in many Eastern cultures invokes feelings of shame and this is felt by any team members who may be directly involved.

Actions or words that are considered disrespectful in Eastern cultures may cause the lowering of a persons’ standing, and this leads to shame in the eyes of peers.

Guilt is adaptive and helpful—it’s holding something we’ve done or failed to do up against our values and feeling psychological discomfort.

Shame is the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of belonging—something we’ve experienced, done, or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection.

Brené Brown Shame vs. Guilt (2013)

In Eastern cultures the impact of ‘Face’ seems to be more pervasive and more nuanced than in Western cultures. In Western cultures, the expression “saving Face” usually means that someone is trying to protect their own interests or reputation. But in Eastern cultures, the phrase is not about covering up mistakes or avoiding accountability, but an intentional and authentic act designed to create a positive outcome for everyone involved (Maya Hu-Chan, 2020).

A reason that differences exist between Western and Eastern understanding of ‘Face’, might be that Eastern cultures value hierarchy, social roles and interpersonal relationships to a higher degree than Western cultures do.

Face can have a much deeper and stronger impact in Eastern cultures than what may be ‘a simple case of personal embarrassment’.

Some examples include:

Some examples include:

The Dutch Project Director explained later that she was aware of the Eastern concept of ‘losing Face’. However, when it came down to something that incensed her ethically, her personal need to prove that she was morally ‘right’ was much stronger than her ability to practice the most culturally sensitive approach. By losing the goodwill and trust of her Asian colleagues, she had effectively lost the ‘deal.’

To be able to effectively practice ‘saving Face’ by raising people’s social standing and self worth, seems to produce much better long-term business outcomes across cultures.

_________________________________________

Joost Thissen, Partner & Interculturalist

joost@cultureresourcecentre.com.au

cultural column  Email This Post

Email This Post