Blog Culture@Work

Welcome! My name is Joost Thissen and here I like to share cultural columns and insights for those of us who are interested in culturally diverse and global workplaces.

Welcome! My name is Joost Thissen and here I like to share cultural columns and insights for those of us who are interested in culturally diverse and global workplaces.

FROM THE LITERATURE. In their book ‘Understanding Social Psychology Across Cultures (2006), the authors Smith, Bond, and Kağitçibasi discuss Berry’s Typology of Acculturation Strategies Model (1997). The model suggest that there are different strategies for migrants to acculturate in the new host culture. The model gave me a lot of food for thought taking into consideration Australia, the country I lived and worked in as a migrant myself since early 1999.

In this article I like to share these strategies, and to explore which one seems to generate the more successful outcome. Furthermore I like to see if we can apply acculturation strategies to working successfully in culturally diverse organisations.

Our identities are rooted in the groups with which we are affiliated, and the way that we compare these groups with other relevant groups. Acculturation is the process of group and individual changes in culture and behaviour that result from intercultural contact.

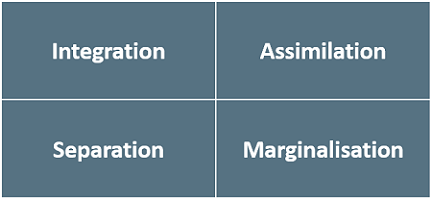

Berry’s Acculturation Strategies

According to Berry, when people arrive in a new country they obviously experiencing difficulties: lack of language skills, lack of former support network, need for accommodation and employment. This can bring personal stress. Berry’s model (2003) positions four acculturation strategies based on the degree to which a migrant wants to maintain the characteristics of their culture of origin (keep heritage culture and identity) and the degree to which a migrant wants to engage with the majority host culture (learn about and interact with new culture):

Migrants are not always completely free to choose their preferred strategy: the attitudes of the majority population, the policies of the new country, and resources available to them can have a major impact. Host cultures might for example not always be welcoming if migrants are perceived as an ‘out-group’ and to be different from their own culture (based on e.g. ethnic, race, religious, socio-economical differences).

Using stereotypes can sometimes help us as a starting point to deal with these differences, however it can lead to prejudice when the stereotype does not fit or does not evolve. According to the authors, prejudice against minorities in societies might also come from perceived threats and wanting to keep existing norms of social dominance by the majority group. Sounds to me like Fear-of-Losing-Control, which might also be one of the founding principle behind racism.

The authors discuss an interesting proposition from Redfield (1936) who believes that acculturation involves changes in not only the migrant group, but both cultural groups in contact: i.e. the migrants and the host culture. They further suggest that we might need to turn to governments and ask what they can do to assist in minimising prejudice, and “create ways in order that the positive contributions available from migrants can be best utilized and that levels of intergroup prejudice can be overcome”. I agree with them that a successful acculturation process is not only the responsibility of the migrant. In fact, the host culture is equally responsible for creating pathways towards positive acculturation which should be within reach of any acculturating individual. Acculturation is a two-way journey.

Integration Strategy

Research shows that by following the integration strategy, acculturating individuals can be expected to experience lower levels of personal stress since they are able to acquire the cultural characteristics of the new culture (as expected by members of the new culture or group) while continuing to value the culture of heritage (as possibly expected by parents, siblings, and friends).

The literature also seems to indicate that migrants who favour integration will acculturate best on a variety of measures of adjustment. Assimilation will still do better than Separation and Marginalisation. It might be worthwhile to consider that the four strategies are not necessarily static but can be part of a process: while someone may want to reject a certain culture at first, they may want to adapt to that culture later on. To summarise: Integration seem to bring less stress and the best acculturation for migrants.

Individuals who deliberately choose the integration strategy in Berry’s acculturation model can be considered bi-cultural. When employed in the host culture, these bicultural individuals are knowledgeable about two cultures and feel perfectly comfortable interacting and working in either culture group.

When Berry’s Integration strategy is applied to culturally diverse organisations, I foresee a possible cultural competitive advantage. Leaders and managers should consider investing in ways to implement the integration strategy: they can start by looking into realigning culturally preferred work practices. Think for example about how different cultures prefer to manage staff, make decisions, build relationships, and communicate with each other. Furthermore they need to develop staff cultural competence to enable them to implement culturally appropriate practices: this will minimise stress and help collaboration between culturally diverse staff. Sounds to me worthwhile exploring a bit further as this might lead to high performance within culturally diverse teams.

Smith P. B., Bond M.H., Kağitçibasi C., (2006). Understanding Social Psychology Across Cultures. Living and working in a changing world. Chapter 11 Cultural Aspects of Intergroup relations

Cultural Column (by Joost Thissen): Bicultural Competent Professionals deliver a Cultural Competitive Edge

_________________________________________

Joost Thissen, Partner & Interculturalist

joost@cultureresourcecentre.com.au

From the literature  Email This Post

Email This Post